MICKI BALABAN, who helped found the Spanish Trail Playhouse in Chipley in 1962 while raising her family on a cattle ranch outside of Bonifay, died on May 4 near her longtime home in Connecticut. She was 94.

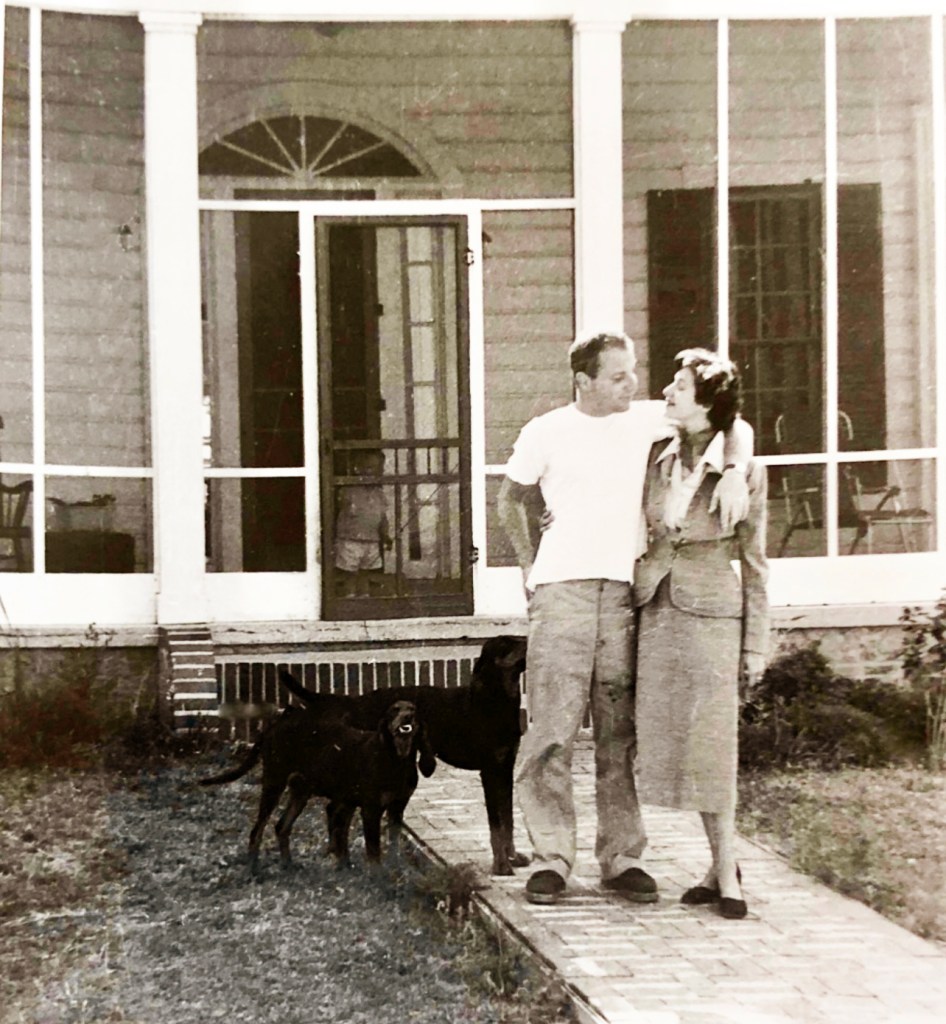

She and her husband Leonard, also known as Red, came to Bonifay in 1952 and bought an 800-acre farm northeast of town on the Poplar Springs Road. They and their children, Mike, Steve and Rachel, became a vital part of the community before moving back north in 1967.

They remained in touch with friends here long after they left. Their farm, which they called Lookout Plantation, was later divided into smaller parcels, but is still known by many as the old Balaban place.

News of her death posted online by her children brought an outpouring of happy memories and comments from around the country, and from Bonifay.

“She was a special lady,” Martha Cullifer Howell commented. “She left her mark on us here in Bonifay.”

“As a child, I would be with my mother when your mother and my mother would visit in the stores in Bonifay,” wrote Amalia Quattlebaum. “Your mother was like a breath of fresh air when she entered a room.”

Wrote retired educator Sheri Curry Brooks: “When we were growing up, I thought she was such a beautiful, exotic lady. I remember her teaching us tap dancing one summer. She was such a fun lady as well as beautiful.”

•

Her son Mike told more of her story:

“Micki Israel Balaban was an only child born in Providence, RI, in 1929, during the Depression. Her family life was a bit suffocating, so she couldn’t wait to become an adult and get away. Marrying my dad accomplished that.

“She was smart and talented. She wrote her high school senior play, starred in all her college theatrical productions at Pembroke College, Brown University’s women’s school, and, as a senior, was offered a Marshall scholarship to study acting at the Young Vic Theater in London. She turned it down.”

Instead, she married Lennie Balaban. They met as students at Brown, in Rhode Island, and later moved to Gainesville, where he studied animal husbandry at the University of Florida extension. He had decided to become a cattle rancher, escaping the expectations of his own family — especially his movie mogul father, Barney Balaban, president of Paramount Pictures. His ranch in Holmes County became renowned for its 300 head of purebred American Angus cattle.

Micki Balaban helped found the Spanish Trail Playhouse and directed and starred in many of its productions before she and her family returned to New England in 1967. The playhouse closed in 1968, but was resurrected in 2006 and continues today.

Micki went on to establish another theater company in Connecticut and became a skilled high school counselor.

Red became a well-known jazz musician, playing the Dixieland jazz he had taught himself on the farm in Bonifay. He led a rotating all-star group at Eddie Condon’s jazz club in Midtown Manhattan, which he owned and operated for a decade.

•

“She was a force,” Rachel Balaban wrote in announcing her mother’s death. “She touched people in profound ways and made them feel seen and heard.”

A celebration of life service will be held in Connecticut in August.

EARLIER: Our own ‘Green Acres’