PERSONAL HISTORY | THOMAS R. REYNOLDS

My first newspaper, The Esto Herald, debuted when I was 15. It was printed on a castoff mimeograph machine I’d rescued from the county dump. I showed a copy to my 10th grade typing teacher, whose encouragement lit a spark. She took Vol. 1, No. 1, home to her husband, the legendary newspaperman E.W. “Judge” Carswell, who covered the heart of the Florida Panhandle for The Pensacola News-Journal. Soon it was splashed, with my photo, across the top of the front page of the Sunday edition.

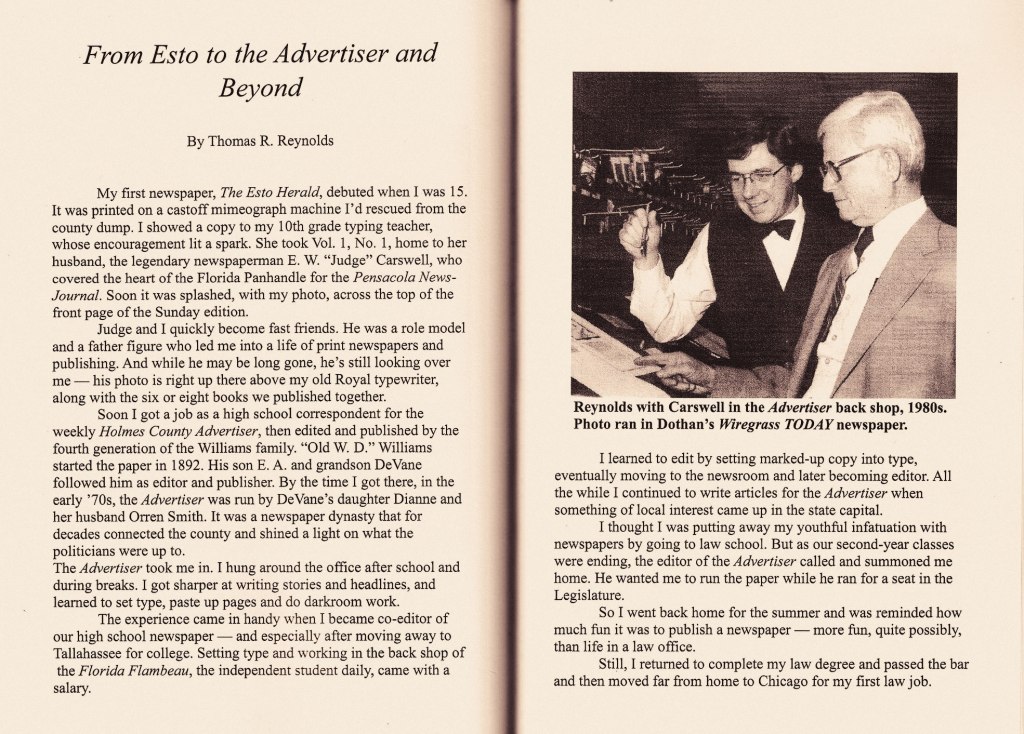

Judge and I quickly become fast friends. He was a role model and a father figure who led me into a life of newspapers and publishing. And while he may be long gone, he’s still looking over me — his photo is right up there above my old Royal typewriter, along with the six or eight books we published together.

Soon I got a job as a high school correspondent for the weekly Holmes County Advertiser, which was then edited and published by the fourth generation of the Williams family. “Old W.D.” Williams started the paper in 1892. His son E.A. and grandson DeVane followed him as editor and publisher. By the time I got there, in the early ’70s, the Advertiser was run by DeVane’s daughter Dianne and her husband Orren Smith. It was a newspaper dynasty that for decades connected the county and shined a light on what the people and the politicians were up to.

The Advertiser took me in. I hung around the office after school and during breaks. I got sharper at writing stories and headlines, and learned to set type, paste up pages and do darkroom work. The experience came in handy when I became co-editor of our high school newspaper — and especially after moving away to Tallahassee for college. Setting type and working in the backshop of the Florida Flambeau, the independent student daily, came with a salary. I learned to edit by setting marked-up copy into type, eventually moving to the newsroom and later becoming editor. All the while I continued to write articles for the Advertiser when something of local interest came up in the state capital.

•

I thought I was putting away my youthful infatuation with newspapers by going to law school. But as our second year classes were ending, the editor of the Advertiser called and summoned me home. He wanted me to run the paper while he ran for a seat in the Legislature. So I went back home for the summer and was reminded how much fun it was to publish a newspaper — more fun, quite possibly, than life in a law office.

Still, I returned to complete my law degree and pass the bar, and then moved far from home to Chicago for my first law job. Being in a big city and living in a high-rise on the lakefront was a great adventure. The work was engaging and I was making new friends. But I was drawn toward reporting and publishing — and toward home.

“Come back before you forget,” Judge wrote. So I did.

For the next five years, Judge Carswell and I ran our own little publishing empire. He’d grown up just south of Esto, my hometown, and he’d been covering our neck of the woods for 50 years by then. He’d found a way to stay at home in our rural area where not much big news ever happened, yet become a respected reporter and columnist for the biggest and best daily newspaper in northwest Florida. He knew the people and the place. He was, he acknowledged, “in the briar patch.”

Judge could write a straight news story, if something actually happened, or spin an entire column about the changing of the seasons.

“One of this area’s non-celebrated harbingers of spring is the water moccasin,” he’d start, and off he’d go.

“Dog Days are upon us,” he began another column. “They comprise summer’s doldrums, a sultry season marked by hot muggy weather that saps life’s ambition right out of a person. Several of my friends, who say I should know about such things, have called to ask when Dog Days will end. I couldn’t even tell them when they began.”

We published a series of books featuring his columns, including Commotion in the Magnolia Tree, He Sold No ’Shine Before Its Time and Tales of Grandpa and Cousin Fitzhugh. We also published a history of our hometown titled Esto: This Is the Place. And then, our most ambitious work, a comprehensive history of Holmes County we called Holmesteading.

As we were getting Holmesteading ready for publication, I was invited to California to interview for a legal publishing job. I went, even though I had no intention of taking the job. Then late one night, back in the Advertiser’s familiar backshop, setting type and pasting up then final pages of our book, I realized I should go.

Judge gave his blessings this time. In his inscription to Holmesteading, he wrote that our collaboration “has made this and other publication adventures possible. And it has been fun. My best wishes go with you always.”

•

Time and fortune were in my favor. Legal journalism was just being born, and I was able to combine both interests. I became editor and publisher of California Lawyer, a monthly magazine. Later we launched the San Francisco Daily Journal, which covered the courts and the legal profession. It was a tough audience and a competitive market, but a fun and rewarding ride.

The best was yet to come. My more talented wife, the lawyer-author Barbara Kate Repa, and I bought The New Fillmore, a community newspaper in one of San Francisco’s finest neighborhoods, where we lived and had become deeply engaged. I ended up with the best of both worlds: our own small town newspaper in heart of a big city filled with interesting people and places.

All along I’ve kept up my subscription to the Holmes County Advertiser, even as it has been passed around among various owners and encroaching chains. It was threatened with competition a few years ago when the owners of the Washington County News in a neighboring county started a rival paper in Holmes County they called the Times. New chain overlords combined the papers as the Times-Advertiser.

That rankled me. Sometimes the paper, under ever-changing ownership — Freedom to Gatehouse to Gannett and others — seemed to have more editors and publishers than local content. Finally yet another new publisher settled on a name change. The paper would be called simply the Holmes County Times.

I nearly jumped out of my chair when the first issue arrived sporting a new nameplate. I wrote an angry email to the new editor decrying the change and canceling my lifelong subscription. Fortunately, I showed it to my wife before sending it. She laughed and said: “You’d die if you didn’t get the Advertiser in the mail every week.”

So I rewrote the email, pointing out the paper had been the Advertiser for more than 100 years by then, and urged them to reconsider.

To her everlasting credit, the new editor called and said: “I think we made a mistake.” And she persuaded the new publisher they should promptly rename it the Holmes County Advertiser, as it has been known since 1892 — at least when it wasn’t called the Aggravator or the Agitator.

Critics used to say: “Read the Advertiser and eat a bowl of grits — you’ll have nothing in your stomach and nothing on your mind.” But I still get excited when the Advertiser lands in our mailbox, especially now that it’s back under local ownership. I still write an article or a column now and then when something from home catches my attention.

And The Esto Herald continues, 55 years after the first issue. But now it’s online.

— Excerpted from Sue Riddle Cronkite’s latest book, “Life in Print News,” available here, which tells the tale of her odyssey at newspapers from Holmes County to Birmingham and back again, with contributions from many others she’s met along the way.