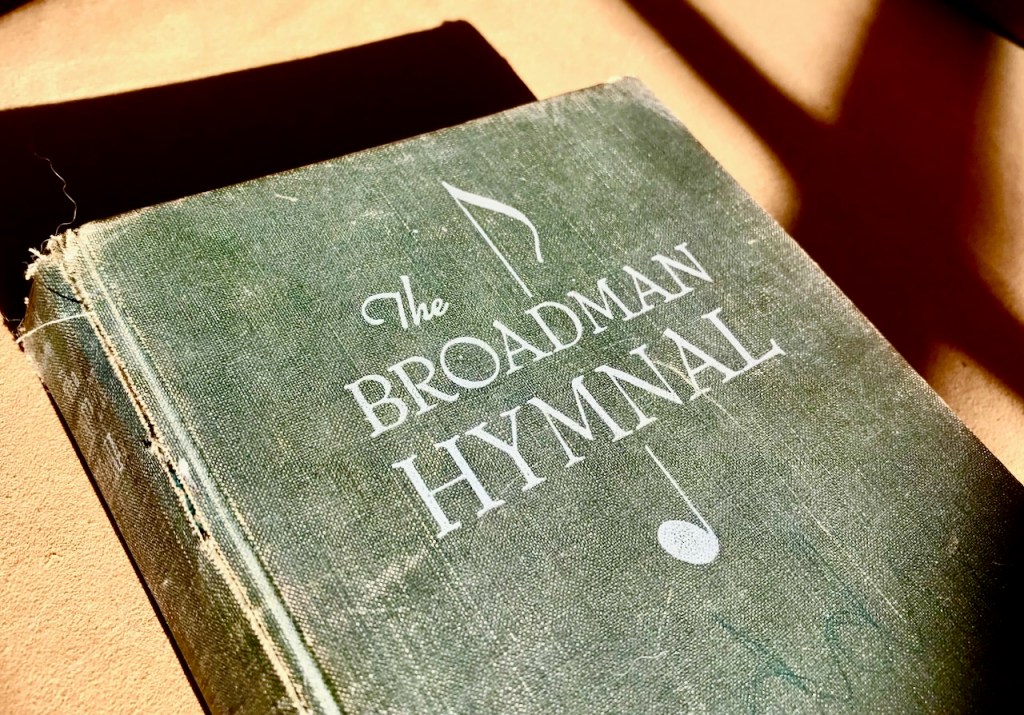

GOSPEL WAS OUR MUSIC when I was growing up in Esto. In addition to church, we often had community sings, and the Biggest All Night Gospel Singing in the World was a major event every Fourth of July weekend, from sundown to sunup, at the football field in Bonifay, the county seat.

When I was a senior in high school, we went to a revival service at First Baptist Church in Bonifay — the big time in Holmes County. It featured traveling evangelists Ed and Bette Stalnecker and their entourage of musicians. I especially loved Bette’s soaring rendition of “His Eye Is on the Sparrow,” a beautiful song not in our hymnal. I found the sheet music and must have played that song hundreds of times on the piano at Esto Baptist Church as the prelude or offertory or benediction hymn.

After I moved all the way to Tallahassee for college, I saw the Stalneckers again at Thomasville Road Baptist Church. The music was still joyous and uplifting, especially “His Eye Is on the Sparrow.” (But you had to wonder about Rev. Ed Stalnecker’s demand at the end of his sermon that 100 people come forward to make a public profession of faith before the doors would be opened.)

I saw and heard the Stalneckers only those two times, but the memory of their music stayed with me. Once when I was back home, I asked retired school principal Kenneth Yates, then and now the organist at First Baptist Bonifay, if he remembered the Stalneckers. Not only did he remember; he had recorded some of their music, and promised to make a copy. I rarely saw Mr. Yates on my trips home that I didn’t ask about the Stalnecker recording. He always assured me he’d find it someday and make a copy. But it never happened. Decades passed.

And now, all of a sudden, it’s here. I went to the post office on Monday and found a yellow notice in our box that we had a package. The desk clerk came back with a small square padded envelope. Return address: K. Yates, Bonifay, FL. Inside was a CD with the inscription: “A Week of Gospel Music: The Stalneckers. FBC Bonifay. February 1973.” Only 49 1/2 years later!

“This is my story, this is my song.”

That’s the full-throated opening chorus of the first hymn, an old favorite. Then “Love Lifted Me” and “Heaven Came Down and Glory Filled My Soul” and “Oh, the Wonder of It All.” And then, on track 10: “His Eye Is on the Sparrow,” every bit as wonderful as I remembered.

That voice! Bette Stalnecker was a contralto, it turns out, with a big deep husky singing voice that sounds almost like a man. Her soft-spoken sweetness and gentle humor come through between songs. At one point she says, “We get a complaint every now and then that we don’t do enough foot-stomping gospel music,” followed by a rollicking version of “Jesus Is Coming Soon.” And then, near the end, everybody’s favorite: “How Great Thou Art.”

I’ve played the CD dozens of times during the past week. A little searching revealed that Ed divorced Bette a few years after I saw them. He found another Betty and another ministry involving donated cars and boats. Allegations of forgery and other wrongdoing preceded his death in 2007.

Bette kept singing in Baptist churches throughout the South, successfully battling the throat cancer that took her voice for almost a year. She remarried, to a longtime family friend, after his wife died. Now, at 93, Bette Stalnecker Gibson is still singing — and on Facebook. A few days ago she posted a video of herself before a senior group in Tennessee. She was singing “His Eye Is on the Sparrow.”

"HIS EYE IS ON THE SPARROW" (2022)

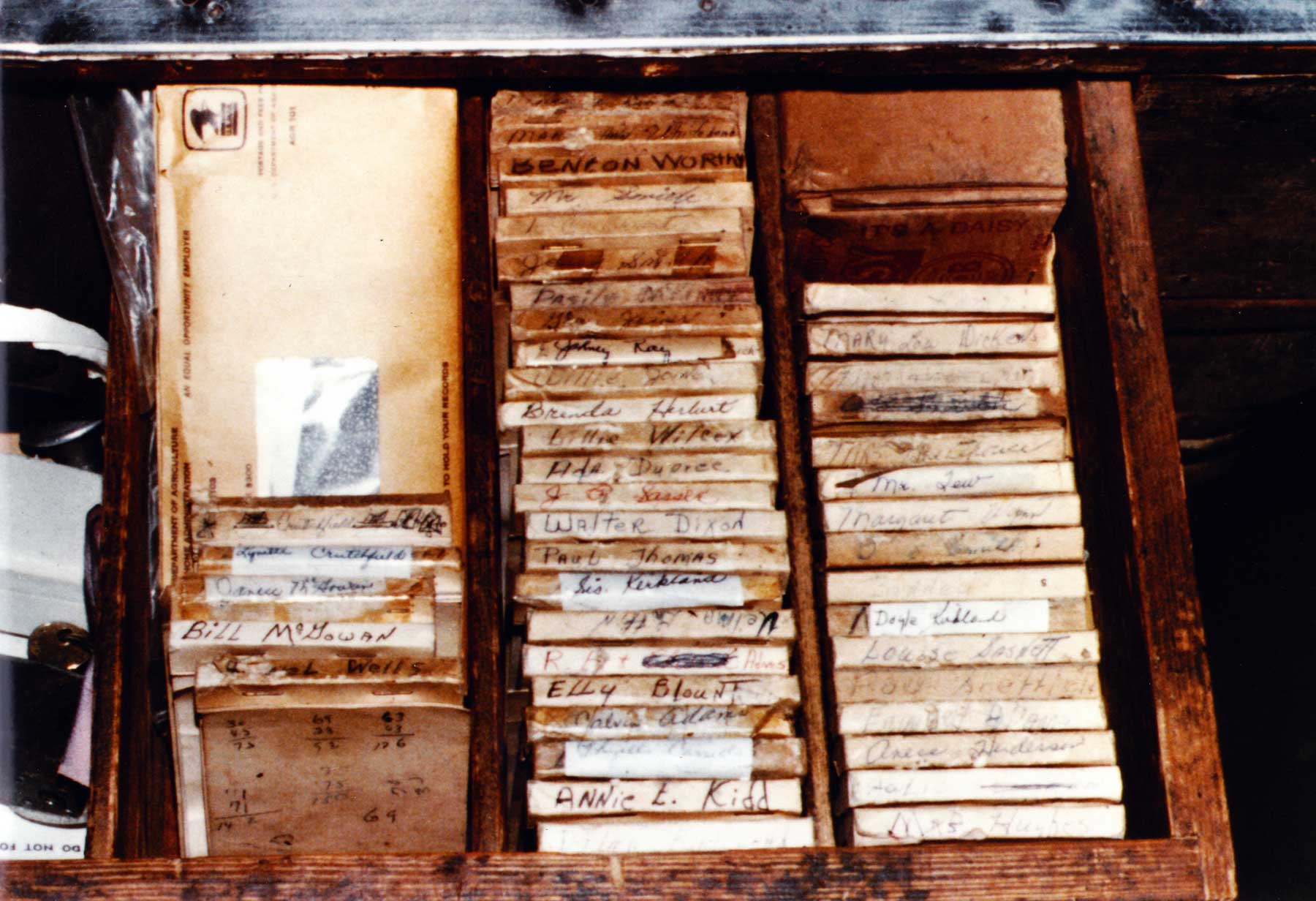

FOR TRUE FANS of gospel music, here is a selection of songs performed by the Stalneckers at First Baptist Church, Bonifay, in February 1973.