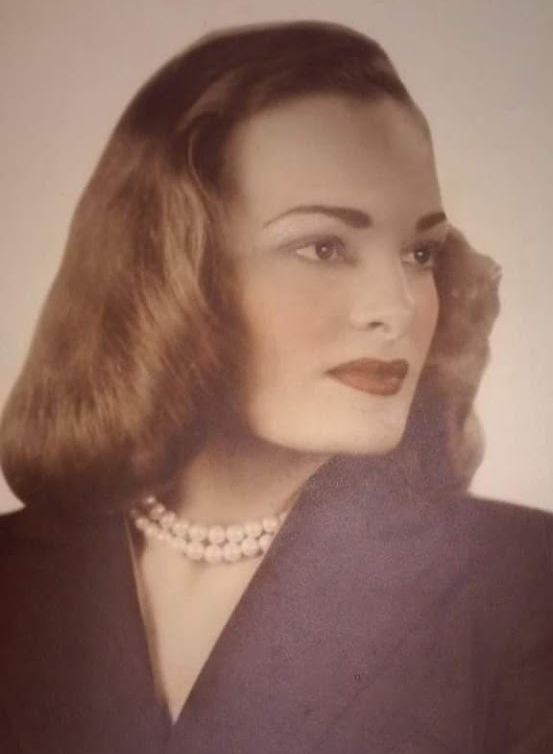

TODAY WAS HER 98th birthday, so I called Sybil Taylor to wish her well and talk about the old days in Esto.

She didn’t answer. A little searching revealed that she died last fall, with no announcement made locally. My Christmas card was not returned.

Sybil Miller Taylor lived almost all of her long life just south of Holland’s Crossroads, where Highway 79 meets Highway 2. She was a devout member of the Esto Church of Christ, absolutely certain of her beliefs and eager to convert others. Late in life, she gave her family farm to Faulkner University, a Church of Christ college in Montgomery, and lived on campus during her final years.

Faulkner University posted this story in its “Supporter Spotlight.”

Sybil Taylor, who passed away October 22, 2021, at the age of 97, wasn’t sure what she would do when her husband Moody Taylor died years earlier and left their farm in Florida to her.

Taylor and her husband had been having financial difficulties with the farm when she heard a sermon on giving and she made a promise to the Lord that she would give half of what she earned to the Lord and his work. She kept her promise and the Lord blessed their farm and increased their revenue.

One night after her husband passed away, Elizabeth Wright Smith, who was one of Faulkner University’s strongest supporters, visited Taylor to share the university’s missions and need for funds. After sharing her story, Smith asked Mrs. Taylor if she would like to support Faulkner University. Her response was quick. At the time, Smith was asking donors to give $1,000 each year for a period of 10 years. The next morning, Taylor gave Smith a check for $10,000.

“I knew about Faulkner University when it first opened in 1942 as Montgomery Bible College and then as Alabama Christian College,” Taylor said. “I received the Gospel Advocate newspaper, as did all my family members before me. When Elizabeth came to ask me for my support, I wanted to give. Faulkner was one of the few Christian colleges I knew about at the time and I wanted to support them.”

Since that day, Taylor was an unwavering supporter and friend of Faulkner University.

When it came time to make a decision about her farm, Taylor, who was well into her retirement years, decided to deed the farm to Faulkner for the university to sell. Funds from the sale went to the university and five charitable gift annuities were set up for Taylor to live on a stable income for the rest of her life. With a charitable gift annuity, Taylor received a return based on her age. This fixed payment was in addition to a large income tax deduction.

She lived on campus for many years before her passing.

A memorial service was held on November 2 at University Church of Christ in Montgomery.