Delma Lee Smith Kirkland (center) with her parents in Esto in the 1920s.

ESTO’S MOST SENIOR CITIZEN — and one of its most beloved — died early Sunday morning, May 17, 2010. Delma Lee Kirkland was 94 and a lifelong resident of Esto.

She had been at home, in bed, for nearly a dozen years, since she had begun to drift away. She spoke only rarely at first, and then not at all. By the end she had stopped even opening her eyes. But someone was always near her side, usually one of her children or grandchildren.

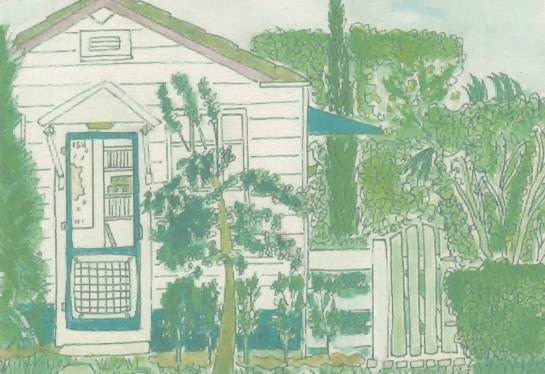

News of her impending death came first on Saturday afternoon to a caretaker as she sat on the screened front porch of the family’s old white wooden house. She said it seemed as if God Himself spoke to say He was going to bring Mrs. Kirkland a blessing. So she went inside to be sure everything was alright. As she repeated what she had heard, Mrs. Kirkland, for the first time in weeks, opened her eyes and looked back, seemingly into her caretaker’s very soul. By morning, her long, lingering journey was over.

Her funeral on Wednesday morning, May 20, brought a full house of friends and flowers to Esto Baptist Church, where Mrs. Kirkland had worshipped all her life. A former son-in-law, Tommy Holman, captured her spirit in his eulogy.

“We got our phone calls early Sunday morning, one week after Mother’s Day, that Nanny had passed away,” he began. “Nanny was the wife of a farmer,” U.T. Kirkland, he said. “She knew her job and she did it well. She raised two children during wartime and she supported the endeavors of her husband until he passed away. She kept a good house and filled the table each meal with good and healthy food.”

Delma Kirkland (center) with daughter Vivian Holman and husband U.T. Kirkland in 1975.

He spoke directly to those who had doubted the family’s decision to keep her at home, in bed, for so many years.

“There are many who would question why it was that Nanny was required to live so many years confined to a bed and fed through a tube,” he said. “There were many who voiced their opinion that Nanny would not want to be there in that condition. There were just as many who questioned why her family did not resign her to a nursing home.”

He had an answer. “Those who questioned did not see what Nanny was giving to her family,” he said. “Even in her nonverbal state Nanny was giving her family a reason to remain a family in these times when so many families have drifted apart.”

Some might also have questioned why it was a former son-in-law delivering the eulogy, one whose divorce had been extremely painful for the family. He had an answer for that question, too, remembering that Mrs. Kirkland had once told him, “I can’t say what’s right or wrong for other people and it’s not my place to judge.”

“That was the way Nanny lived her long life,” he said. “She worked hard, she loved devotedly, she accepted unconditionally, she cried some, but she laughed much.”

Her capacity for love was brought home powerfully just as the funeral was beginning when a group from the Association for Retarded Citizens in Chipley, where Mrs. Kirkland had worked later in her life, entered the church.

“She helped and encouraged challenged individuals toward a better life,” her ex-son-in-law said. “She was a natural at this job because it was ever her way to help and to encourage others. This job came as natural to her as her smile and her jovial laughter.”

Despite the loss of a neighbor they had known all their lives, many in the crowd that filled the church had smiles on their faces and a humorous story to share as they moved outside for the graveside farewell.

Afterward, a bounteous old-fashioned dinner on the grounds awaited inside the church’s air-conditioned fellowship hall.

“I think she would have loved her funeral,” said Annie Laura Kidd, Mrs. Kirkland’s 85-year-old first cousin and “sister of the heart,” as the obituary noted, who clutched a rose from her lifelong friend’s casket. “She always said she wanted a lot of pretty flowers.”

VIMEO | Delma Kirkland and Annie Laura Kidd remember picking violets when they were little girls.